Call me a safe bet, I’m betting I’m not

I’m glad that you can forgive

Only hoping as time goes, you can forget-Brand New, The Boy Who Blocked His Own Shot

One of the great ironies of life is we have a strong tendency to play it safe, even if it costs us the win.

The issue stems from a cognitive bias called loss aversion, where the pain of loss is felt twice as intensely as an equivalent gain. Imagine finding $20 on the street only to have it blown out of your hands by a strong gust of wind. Economically, you’re in no worse a spot than before you found the money, but you feel worse because it feels like you lost $20 ($20 gain - $40 loss).

When triggered, this predilection for avoiding a loss causes us to conflate safety with success. While the two can lead you to the same choice, they aren’t synonymous.

The safe choice is nestled in averages. As the old saying goes, there’s safety in numbers, so when threatened, we look to conform with what most people would do in our shoes. There’s little, if any, upside to be had because we’re seeking the herd's protection rather than leading the pack.

That’s not to say there isn’t value in using common sense. Sometimes adequate is sufficient. This gets us in trouble when there’s dissonance between what we want and the behaviors we exhibit. When we want to be great but we deliver average.

Howard Marks, co-founder/co-chairman of Oaktree Capital Management, penned this simple but insightful 2x2 in his memo, Dare to Be Great.

His overarching point is that superior results require a synthesis of unconventionality and accuracy, as payoffs can only be high when a select few are particularly prescient. This is effectively the Pareto principle in action - 20% of the activity will deliver 80% of the results.

What goes unnoticed, though, is how appealing the bottom two quadrants are. Sure, you can’t be elite by following the consensus, but delivering average on a consensus position is defensible. It’s safe. If your goal is to maintain the status quo, you’re better off sticking with the like-minded masses rather than venture outside-the-box with the non-consensus few.

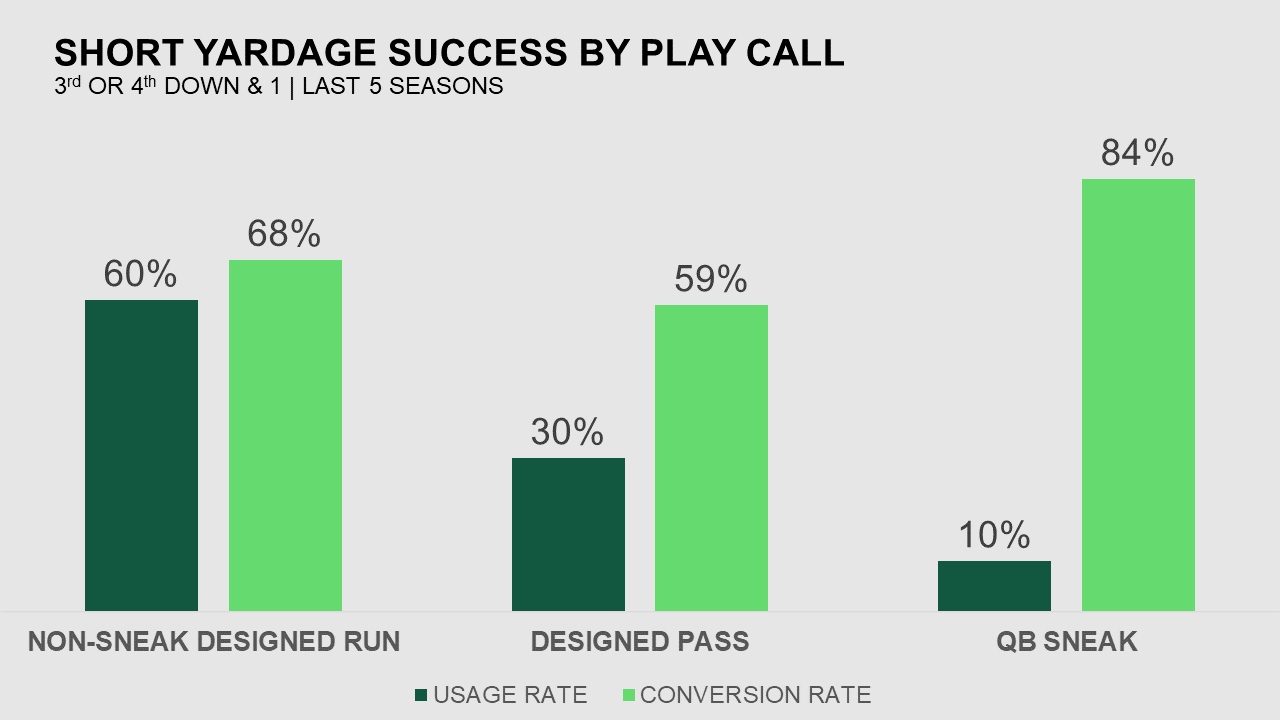

To see how this plays out in practice, consider NFL play-calling. Winning in the NFL is hard, but you can improve your odds by keeping the opposing offense off the field. When faced with converting a short-yardage situation where success means keeping possession of the ball, having the quarterback (QB) run behind the offensive line has resulted in a first down 84% of the time over the last five years. There are not many guarantees in life, but with those odds, it’s about as close as you’ll come in a game of skill.

And yet, coaches have only used that formation 10% of the time.

What’s happening here? Nine times out of ten, NFL coaches call a play with a significantly lower success rate than the QB sneak. One could argue that the play is so effective because it’s used infrequently, but it’s hard to imagine a play-calling strategy with a higher mix of QB sneaks wouldn’t result in a net increase in first downs.

In these high-pressure moments, it’s doubtful that the coach doesn’t want to win. Here, loss aversion is likely still in play, but it’s not the game they’re worried about; it’s their job.

The quarterback is arguably the most valuable player on the field, and putting them in harm’s way is a good way to get put on the hot seat. The sneak is significantly safer than a dropback pass where the quarterback is exposed to open-field or blindside hits where injury risks are significantly higher, but it’s not statistics that stand out in our minds; it’s frequency. If your quarterback gets hurt on a common play, the masses will consider it an unfortunate event but a risk of the game. But if someone gets hurt on a play rarely seen, it’s easier to blame the play call than probability.

Said another way, you may lose the game by being conventional, but you reduce the chance of falling into non-consensus/wrong where you have a greater probability of being fired.

When our livelihood is on the line, it’s easier to chase the herd than lead the pack.

The point is this: if your goal is above-average results, you can’t do it by chasing safety. These cautious approaches will be defensible, perhaps even intuitive, but they have almost no chance of delivering the desired outcomes.

If you’re looking for above-average results to be delivered, here are some signs to watch out for that those executing are chasing the safety of average:

Too little spread over too much - when there are multiple priorities and not enough resources to serve them adequately, you’re staring at someone who is hedging their bets. These priorities will be attractive - must-haves, even - but the reality is they can’t all be delivered. They're implicitly counting on showing activity as a sign of progress rather than delivering outcomes. Success requires heavy effort across a narrow plane, so ruthless prioritization and agile experimentation are key.

Data as a delay tactic - loss aversion will create a strong desire for data to narrow the uncertainty, either in practice or in theory, by generating consensus among stakeholders. This is good up to a point but can quickly become unproductive. Data isn’t prescriptive, nor is it the truth, so when the desire for more data becomes less about guiding the strategy and more about strengthening conviction into something you’ve already committed to, you’re wasting time. Think of data as mile markers to guide your journey rather than essentials to pack before you embark.

“We’re gonna learn” - any test whose objective is “we’re gonna learn” isn’t a test; it’s a waste of resourcing. Running a test without an expected result in mind is like plotting a road-trip without considering where you want to go - the act of driving somewhere doesn’t teach you anything about where you’re headed! Learning requires a falsifiable expectation - something that can surprise you and cause you to rethink how you see the world. Without an expectation, everything that happens is reasonable, and, ultimately, any signs of failure will be missed or discarded. Failure is scary, but it’s critical when breaking from the herd. The quicker you can determine if your strategy is wrong, the quicker you can adapt to maximize your opportunity for above-average outcomes.

If you enjoyed this post from Dollars & Sense by Taylor Otstot, why not subscribe/share?